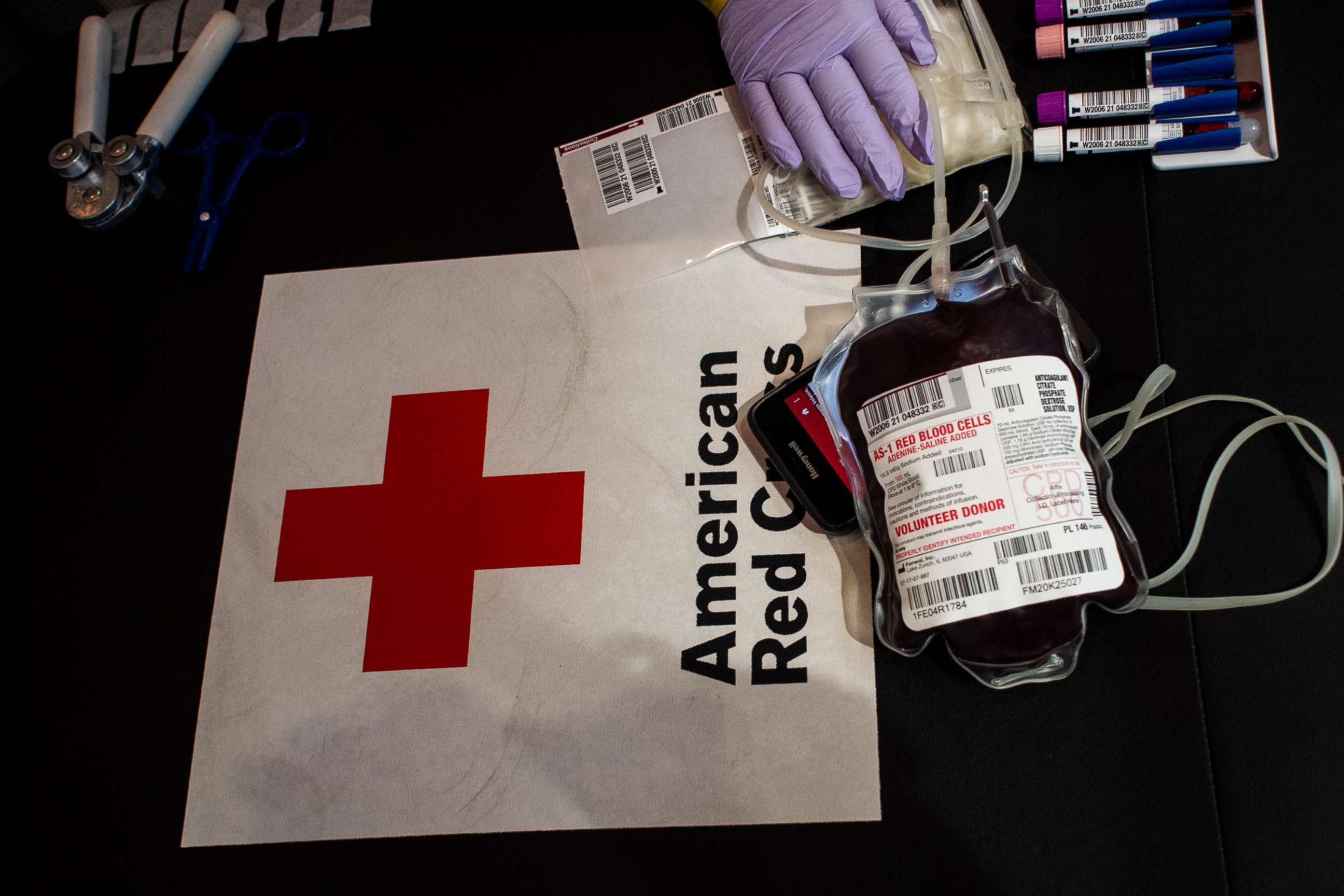

Severe national blood shortage may force doctors to augment patient care, officials say

"The current situation ... is the most concerning I have seen in my career."

As the COVID-19 pandemic comes to a close, more Americans are seeking medical care -- only to find roadblocks to long-awaited elective surgeries or unexpected traumatic injuries: a critical national shortage of blood.

In June, the blood supply dropped to "red" level, indicating dangerously low supply at blood centers nation-wide, according to the AABB Interorganizational Task Force on Domestic Disasters and Acts of Terrorism.

Donated blood products have always been in high demand in the United States. But now, doctors say, the crisis has reached a new, critical turning point, forcing some to triage medical care, reserving blood products only for the sickest patients.

According to the Red Cross, the supplier of 40% of the nation's blood supply, nearly 7,000 units of platelets and 36,000 units of red blood cells are needed daily. On average, an American needs blood products every two seconds.

Patients with certain diseases, such as sickle cell disease and cancer, may require frequent transfusions throughout their lives. A single-car accident victim, per the Red Cross, can require up to 100 units of blood.

"From a personal experience, as someone who has worked in the transfusion medicine field for many years, the current situation with the blood supply is the most concerning I have seen in my career," said Dr. Claudia Cohn, chief medical officer of the American Association of Blood Banks.

The COVID-19 pandemic and recent rise in violent crime has put additional pressure on an already strained blood supply. In comparison to 2019, the demand for blood has climbed by 10% in hospitals with trauma centers and by more than five times in other facilities that provide transfusions, according to the Red Cross.

Now that pandemic restrictions are easing, more patients are returning to the hospital and rescheduling surgeries and medical procedures that were postponed during the pandemic. Meanwhile, the prevalence of gunshot wounds, while slightly lower since the height of the pandemic, remains increased compared to pre-COVID numbers.

In the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area, the incidence of gunshot wounds is "significantly higher than it was prior to COVID," said Dr. Babak Sarani, director of trauma and acute care surgery and co-medical director of critical care at the George Washington University Hospital.

"The types of traumas that require transfusions are persistently remaining up," Sarani said.

The newfound demand is outpacing the already depleted supply. In a typical year, school blood drives contribute a significant amount of blood to the national patient population. Meanwhile, fewer Americans were available to donate blood during lockdown.

"Over the last three months, the Red Cross has distributed about 75,000 blood products more than expected to meet hospital needs, significantly decreasing our national blood supply," said Jessa Merrill, director of biomedical communications at the Red Cross. "In recent weeks, the Red Cross has operated with less than a half a day supply of Type O blood, which is the most-needed blood group by hospitals."

"Some blood collections facilities have reported declines by as much as 50% below normal levels," added Cohn.

Blood shortages are not uncommon. Previous shortages, most notably in 2006, as reported by ABC News, have been significant enough to cause the cancellation of elective surgeries in Los Angeles, Philadelphia and Atlanta.

This critical shortage, however, is dramatically different.

"The majority of blood centers are now reporting a one-day supply or less of blood, far below the levels for which they normally strive. Since we are already experiencing a critical shortage at the beginning of summer, many blood centers are concerned that we will face chronic severe shortages all summer," said Cohn.

The stark decline in blood products could affect many Americans.

"When blood supply is less than adequate, patients may be affected," said Cohn. "It means blood may not be available for all patients when it is needed, leading to suboptimal care for some patients."

Due to shortages, doctors are being forced to reevaluate whether patients deserve blood products.

"We're screening based on criteria that has kicked in because now we're in a critical situation with all of our products," said Dr. Xiomara Fernandez, medical director of transfusion medicine and coagulation at the George Washington University Hospital. "Any orders that don't meet our thresholds, so if anyone has a platelet count above 50 [and a platelet transfusion is ordered], that is definitely a red flag."

Many hospitals may be forced to re-triage patients to ensure an adequate supply of blood products for patients in need.

"Last weekend I had the medical director from Washington Hospital, who was also a trauma center, calling me for help," said Fernandez. "She was afraid that, because of their inventory, if they had a trauma coming in, could they send them to us. Could our blood supply support it? Other medical directors have reached out to me and we're tightly monitoring our inventory."

If the shortage continues, elective surgeries may be canceled. Cancer patients requiring chemotherapy, and the blood transfusions that chemotherapy necessitates, may need to reschedule their lifesaving treatments.

"We are certainly very concerned about the current shortage," said Dr. Craig Bunnell, chief medical officer of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. "We join all other health care institutions in encouraging the public to respond to this national emergency."

"Blood is a critical, lifesaving therapy for millions of patients throughout the world -- and the only source of blood is the generosity of donors," said Cohn. "We have a long summer ahead of us and making sure the blood supply is adequate beyond this week or next is [a] challenge."

To find the nearest site to donate blood, visit AABB's website and use the Blood Donation Site Locator. Your donation could save a life.

Natalie S. Rosen, M.D., is an internal medicine resident physician at The Johns Hopkins Hospital and a contributor to the ABC News Medical Unit.